The Complete Regional Guide to Morocco: A Journey Through the Kingdom’s Diverse Landscapes

The morning mist still clings to the Atlas peaks when I watch my students in Agdz point toward the mountains and tell me about their cousins in Imlil, their aunts in the Rif, their dreams of seeing the Mediterranean.

Teaching in the Draa Valley for five years taught me something profound about Morocco: this isn’t just one country, but a tapestry of distinct regions, each with its own climate, culture, and character.

My grandfather used to say that understanding Morocco means understanding its mountains, valleys, and coasts as separate chapters in the same beautiful story.

After countless weekend explorations, volunteer work across different provinces, and conversations with locals from Tangier to Laayoune, I’ve come to appreciate how dramatically Morocco’s geography shapes its people, traditions, and daily rhythms.

Whether you’re planning a comprehensive Morocco journey or trying to choose which region calls to your heart, understanding these distinct areas will transform how you experience the kingdom.

High Atlas Mountains: Morocco’s Backbone

The High Atlas forms Morocco’s spine, stretching 700 kilometers from the Atlantic coast to the Algerian border. Living in the shadow of these peaks in Agdz, I’ve learned to read their moods through the clouds that gather around Jebel Toubkal, North Africa’s highest summit at 4,167 meters.

The western High Atlas, accessible from Marrakech, offers the most developed trekking infrastructure. The Toubkal circuit remains the crown jewel, but I always recommend the quieter Azzaden Valley for those seeking authentic Berber hospitality without the crowds. In spring, when the snow melts and wildflowers carpet the valleys, the contrast between the red earth and snow-capped peaks creates landscapes that still take my breath away after years of familiarity.

High Atlas Mountains

Morocco’s Backbone – 700km of Peaks and Valleys

Geographic Overview

Jebel Toubkal

4,167m – North Africa’s highest peak

Water Tower Role

Snowmelt feeds khettaras supporting desert oases

Ecosystem Diversity

From Mediterranean valleys to alpine zones

From Othmane’s Perspective

“Living in the shadow of these peaks in Agdz, I’ve learned to read their moods through the clouds that gather around Toubkal.”

“In spring, when wildflowers carpet the valleys, the contrast between red earth and snow-capped peaks still takes my breath away.”

Western High Atlas

Key Highlights:

Central High Atlas

Key Highlights:

Eastern High Atlas

Key Highlights:

Spring in the High Atlas

Seasonal Highlights

Wildflower blooms, snow melt, perfect trekking

Water Availability

Peak water availability

Cultural Connections Across Morocco

“This connection between mountain and desert, between Berber highlanders and Arab oasis dwellers, illustrates Morocco’s fundamental geographic unity despite its regional diversity.”

Water Systems

Ancient khettaras channel Atlas snowmelt to desert oases

Migration Patterns

Berber families move livestock seasonally between altitudes

Trade Routes

Historic passes connected Sahara trade to Atlantic ports

Traditional Knowledge Systems

Khettara Networks

Underground channels carrying Atlas snowmelt to oases like Agdz, some over 1000 years old

Transhumance Patterns

Seasonal livestock movement between high summer pastures and valley winter grounds

Terraced Agriculture

Centuries-old terrace systems maximizing arable land on steep mountain slopes

Weather Reading

Traditional knowledge of cloud patterns, wind directions, and seasonal signs

The central High Atlas, around the Ait Bougmez Valley, preserves traditional agropastoral life largely unchanged by tourism. Here, you’ll witness seasonal migration patterns that have continued for centuries, with families moving their livestock between summer and winter pastures. The eastern reaches, near Midelt, transition into drier, mineral-rich terrain where the mountains begin their descent toward the Sahara.

Understanding the High Atlas requires appreciating its role as Morocco’s water tower. The ancient irrigation systems, or khettaras, that sustain oasis communities like mine in Agdz originate from snowmelt in these peaks. This connection between mountain and desert, between Berber highlanders and Arab oasis dwellers, illustrates Morocco’s fundamental geographic unity despite its regional diversity.

Middle Atlas Mountains: Morocco’s Switzerland

The Middle Atlas surprised me during my first teaching exchange in Ifrane. Rising gradually from the plains, these mountains create Morocco’s most temperate climate, earning Ifrane the nickname “Little Switzerland.” Unlike the dramatic verticality of the High Atlas, the Middle Atlas rolls in gentle curves, covered in cedar forests that shelter Morocco’s last Barbary macaque populations.

The region divides into distinct zones. The limestone plateaus around Ifrane and Azrou support extensive cedar forests and serve as Morocco’s premier ski destination at Michlifen. The volcanic landscapes near Sefrou create different microclimates, supporting cherry orchards that bloom spectacularly each spring. Moving eastward, the mountains become more arid, transitioning into the high plains that lead toward the Algerian border.

What makes the Middle Atlas unique is its year-round habitability. Unlike the High Atlas, where winter snows force seasonal migration, Middle Atlas communities maintain permanent settlements. The Berber tribes here developed different architectural styles, using local stone rather than the adobe construction common in drier regions. Their market towns like Azrou and Khenifra blend Berber, Arab, and French colonial influences in ways that reflect the region’s position as a cultural crossroads.

The Middle Atlas also contains Morocco’s largest freshwater lakes. Aguelmam Azigza and Aguelmam Sidi Ali create rare wetland ecosystems that support migrating birds and endemic fish species. These lakes, formed by volcanic activity, demonstrate how Morocco’s geological diversity creates distinct ecological niches within relatively small areas.

Anti-Atlas Mountains: Gateway to the Desert

The Anti-Atlas forms Morocco’s most mysterious mountain range, stretching from the Atlantic near Agadir to the edge of the Sahara. Teaching students from Anti-Atlas villages gave me insights into this region’s unique character. Unlike their High Atlas neighbors, Anti-Atlas communities developed cultures adapted to aridity and isolation, creating distinctive traditions in architecture, agriculture, and social organization.

The western Anti-Atlas, centered on Tafraout, showcases the region’s geological wonders. Pink granite formations create landscapes that feel almost Martian, especially when almond blossoms add white accents to the pink rock in February and March. The Painted Rocks of Tafraout, created by Belgian artist Jean Verame, might seem artificial, but they actually highlight the natural color variations in the granite that locals have always recognized.

Moving eastward, the Anti-Atlas reveals its role as a bridge between Mediterranean Morocco and the Sahara. The Jebel Sirwa massif, reaching 3,305 meters, supports saffron cultivation around Taliouine. This represents one of Morocco’s most successful adaptations of traditional agriculture to challenging mountain environments. The volcanic soils and altitude create perfect conditions for saffron, making this region globally significant for spice production.

The eastern Anti-Atlas, approaching Ouarzazate, demonstrates how mountains can create oases. The Draa River, which sustains my home region, originates from Anti-Atlas watersheds. Understanding this connection helped me appreciate how mountain geography creates the ribbon of green that extends south toward the Sahara, supporting communities along the ancient trans-Saharan trade routes.

Sahara Desert: Morocco’s Southern Kingdom

The Moroccan Sahara encompasses nearly two-thirds of the country’s territory, yet most visitors experience only its northern edges around Merzouga and M’hamid. Teaching in Agdz, at the interface between oasis and desert, taught me to see the Sahara not as empty wasteland but as a complex ecosystem supporting diverse communities and traditions.

The Sahara’s northern margin, where I live, consists of stone desert, or hamada, punctuated by seasonal lakes called sebkhas. When winter rains fill these depressions, they create temporary wetlands that support migrating birds and allow ephemeral vegetation to bloom. This cycle of abundance and scarcity shaped the seasonal movements of nomadic communities for millennia.

The great sand seas, or ergs, occupy relatively small portions of the Moroccan Sahara. Erg Chebbi near Merzouga and Erg Chigaga near M’hamid represent the classic dune landscapes that most travelers seek. However, the rocky plateaus and mountain ranges that dominate the desert interior contain equally fascinating landscapes. The Jebel Bani range creates a series of escarpments that channel occasional rainfall into ephemeral rivers, creating linear oases that supported caravan routes.

The Atlantic Sahara, extending south from Laayoune to Lagouira, presents a different character entirely. Here, the desert meets the ocean, creating unique coastal ecosystems. Cold Atlantic waters moderate temperatures and create frequent fog that supports specialized plant communities adapted to maritime desert conditions. This region’s fishing communities developed cultures distinct from both inland desert peoples and Mediterranean coastal populations.

Understanding the Sahara requires recognizing its role in Morocco’s history. The desert wasn’t a barrier but a highway, connecting Morocco to sub-Saharan Africa through trade routes that brought gold, slaves, and Islamic scholarship northward while carrying Moroccan goods and culture southward. The preserved ksour, or fortified villages, along these routes tell stories of prosperity built on trans-Saharan commerce.

Atlantic Coast: Morocco’s Western Gateway

Morocco’s Atlantic coastline extends over 1,800 kilometers from Tangier to Lagouira, creating the country’s longest regional boundary. Having grown up in Casablanca and spent time in different coastal cities through my volunteer work, I’ve come to appreciate how the Atlantic shapes Moroccan culture in ways that distinguish it from purely Mediterranean Arab countries.

The northern Atlantic coast, from Tangier to Casablanca, represents Morocco’s most developed region. The Gharb Plain behind this coastline contains Morocco’s most fertile agricultural land, watered by the Sebou River and supporting intensive cultivation of cereals, citrus, and industrial crops. Cities like Rabat and Casablanca grew at river mouths that provided natural harbors, combining agricultural wealth with maritime trade opportunities.

The influence of Atlantic weather patterns extends far inland, moderating temperatures and bringing winter rainfall that supports agriculture without irrigation. This climatic advantage allowed the development of Morocco’s largest cities and most complex urban cultures. The architectural styles of coastal cities reflect this maritime orientation, with buildings designed to capture sea breezes and resist salt corrosion.

South of Casablanca, the Atlantic coast transitions to more arid conditions. Cities like El Jadida and Safi developed around Portuguese trading posts, creating unique architectural fusions that distinguish them from Arab-founded inland cities. The fishing communities along this coast developed specialized techniques for Atlantic species and created culinary traditions centered on fresh seafood rather than the preserved fish common in Mediterranean Morocco.

The southern Atlantic coast, from Essaouira to Dakhla, reveals the ocean’s increasing dominance over continental influences. Trade winds create consistent conditions that support both traditional fishing and modern windsurfing and kitesurfing tourism. The argan forests behind Essaouira represent unique ecosystems adapted to Atlantic fog and wind, producing Morocco’s liquid gold that has become globally recognized.

Mediterranean Coast: Morocco’s Northern Window

Morocco’s Mediterranean coastline, though shorter than its Atlantic coast, serves as the country’s primary connection to Europe and the broader Mediterranean world. My exchanges with teachers from Tetouan and Al Hoceima revealed how Mediterranean influences create cultural patterns distinct from Atlantic or Saharan Morocco.

The Strait of Gibraltar, only 14 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, has made northern Morocco a constant interface between Europe and Africa. This proximity created unique architectural styles, culinary traditions, and social customs that blend Andalusian, Berber, and Arab influences. The medinas of Tetouan and Chefchaouen preserve Andalusian refugee traditions dating to the Christian reconquest of Spain, creating living museums of Moorish culture.

The Rif Mountains rise directly from the Mediterranean, creating dramatic coastal landscapes and isolating the region from interior Morocco. This geographic isolation allowed the development of distinct Berber cultures and, more recently, economic activities that sometimes conflicted with central government policies. Understanding the Mediterranean coast requires recognizing these tensions between regional identity and national integration.

The eastern Mediterranean coast, approaching the Algerian border, represents Morocco’s most politically sensitive region. The Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla create complex border dynamics that affect local communities in ways that casual tourists rarely appreciate. Economic opportunities in agriculture, fishing, and cross-border commerce shape daily life in patterns distinct from other Moroccan regions.

Climate differences between the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts create different agricultural possibilities. Mediterranean Morocco supports different crops and follows different seasonal rhythms, with summer drought rather than winter rain limiting agricultural activity. These climatic patterns connect northern Morocco to broader Mediterranean agricultural traditions while distinguishing it from Atlantic Morocco’s more temperate patterns.

Rif Mountains: The Northern Highlands

The Rif Mountains create Morocco’s most isolated and culturally distinct region. Rising steeply from the Mediterranean coast and extending eastward toward Algeria, the Rif forms a natural barrier that has preserved unique Berber cultures while complicating national integration efforts.

The central Rif, around Chefchaouen, combines dramatic mountain scenery with distinctive blue-painted architecture that has become iconic in Moroccan tourism. However, the blue paint tradition actually reflects practical concerns about temperature control and insect management rather than purely aesthetic choices. The steep mountain slopes forced the development of terraced agriculture and distinctive architectural techniques for building on challenging terrain.

The eastern Rif, extending toward Al Hoceima and beyond toward the Algerian border, presents even more rugged geography. Here, isolated valleys preserved distinct Berber dialects and traditional customs that differ significantly from other Moroccan regions. The combination of geographic isolation and political marginalization created economic challenges that regional development efforts are slowly addressing.

Cannabis cultivation in certain Rif areas has created complex social and economic dynamics that affect the entire region. Understanding the Rif requires recognizing how geographic isolation, limited economic alternatives, and traditional agricultural practices interact with national and international drug policies. Recent legalization efforts for industrial hemp represent attempts to provide legal alternatives while respecting traditional practices.

The Rif’s position between Mediterranean and continental climate zones creates unique ecosystems. Cedar and fir forests at higher elevations contrast with Mediterranean vegetation at lower altitudes, supporting biodiversity found nowhere else in Morocco. These forests provide ecosystem services including watershed protection and carbon sequestration that benefit broader regions.

Souss Valley: Morocco’s Agricultural Heart

The Souss Valley, extending inland from Agadir between the High Atlas and Anti-Atlas mountains, represents Morocco’s most productive agricultural region outside the northern plains. My work with development projects exposed me to the intensive agricultural systems that make this valley crucial to Morocco’s food security and export economy.

The Souss River creates an alluvial plain exceptionally suited to intensive agriculture. Modern irrigation systems allow year-round cultivation, producing vegetables and citrus fruits for European markets during winter months when local production is minimal. This agricultural success created prosperity that transformed traditional market towns like Taroudant into commercial centers serving extensive rural hinterlands.

The valley’s position between mountain ranges creates a unique microclimate. The High Atlas blocks northern weather systems while the Anti-Atlas provides some protection from Saharan heat and drought. This intermediate position allows cultivation of both temperate and subtropical crops, maximizing agricultural diversity within a relatively small area.

Berber communities in the Souss developed sophisticated water management techniques adapted to seasonal river flows and limited rainfall. Traditional irrigation cooperatives, called khettaras, continue operating alongside modern drip irrigation systems, demonstrating how traditional knowledge complements contemporary technology. These water management traditions influence social organization and legal systems in ways that distinguish the Souss from regions with different hydrological conditions.

The argan forests that cover much of the Souss Basin represent globally unique ecosystems. These trees, found nowhere else in the world, support rural women’s cooperatives that produce argan oil while maintaining forest cover that prevents desertification. The integration of forest conservation, women’s economic empowerment, and international marketing demonstrates innovative approaches to sustainable development.

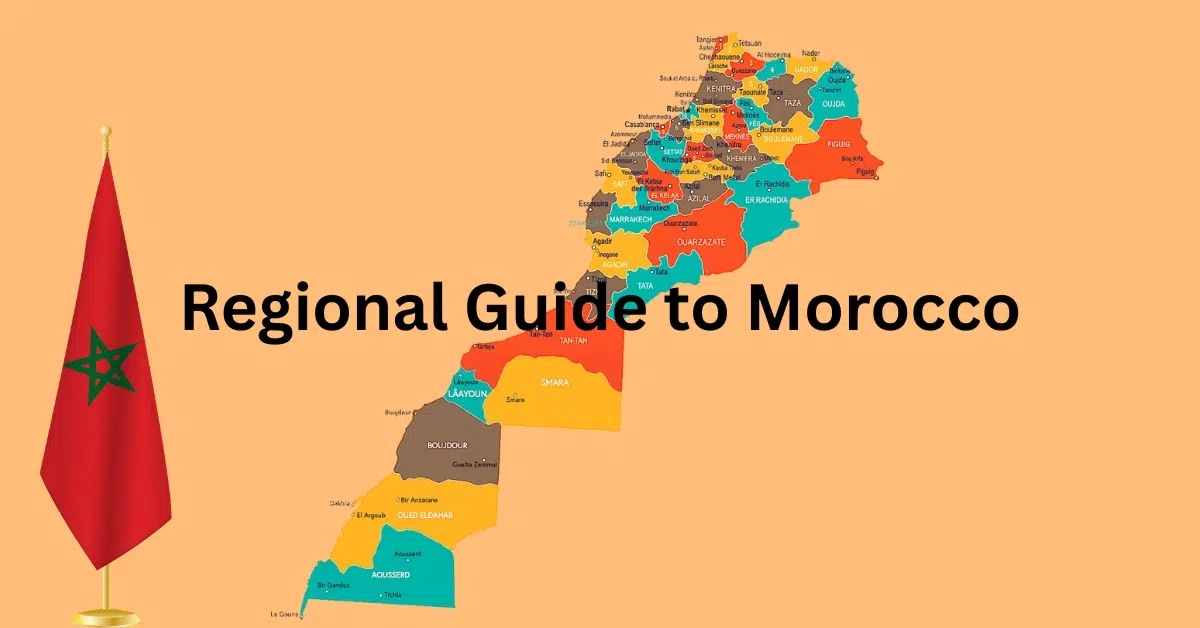

Morocco’s Regions

Explore Morocco’s 12 administrative regions from a local perspective

Click on a region to explore

Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceïma

Northern Coast

L’Oriental

Eastern Border

Fès-Meknès

Imperial Cities

Rabat-Salé-Kénitra

Capital Region

Béni Mellal-Khénifra

Middle Atlas

Casablanca-Settat

Economic Hub

Marrakech-Safi

Tourist Center

Drâa-Tafilalet

Desert Gateway

Souss-Massa

Atlantic South

Guelmim-Oued Noun

Southern Desert

Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra

Western Sahara

Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab

Far South

Select a region above to explore its cities, culture, and economy

Select a Region

| Region | Population | Area (km²) | Capital | Main Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casablanca-Settat | 6.9M | 20,166 | Casablanca | Finance & Industry |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 4.6M | 18,194 | Rabat | Government & Agriculture |

| Fès-Meknès | 4.2M | 40,075 | Fès | Crafts & Agriculture |

| Marrakech-Safi | 4.8M | 39,167 | Marrakech | Tourism & Agriculture |

| L’Oriental | 2.3M | 82,820 | Oujda | Mining & Trade |

| Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceïma | 3.6M | 15,090 | Tangier | Ports & Manufacturing |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | 2.5M | 28,374 | Béni Mellal | Agriculture & Mining |

| Marrakech-Safi | 4.8M | 39,167 | Marrakech | Tourism & Agriculture |

| Souss-Massa | 2.7M | 51,642 | Agadir | Agriculture & Tourism |

| Guelmim-Oued Noun | 433K | 46,108 | Guelmim | Livestock & Trade |

| Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra | 367K | 142,865 | Laâyoune | Fishing & Phosphates |

| Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab | 142K | 50,880 | Dakhla | Fishing & Tourism |

Oriental Region: Morocco’s Eastern Gateway

The Oriental Region, centered on Oujda near the Algerian border, represents Morocco’s least touristed area despite containing diverse landscapes and rich cultural traditions. My volunteer work in this region revealed how geographic position shapes cultural patterns in ways that distinguish eastern Morocco from other regions.

The northern Oriental Region consists of high plains that extend across the Algerian border, creating cultural continuities that transcend national boundaries. Traditional pastoral systems moved livestock seasonally across these plains without regard to modern borders, creating social networks that recent border restrictions have complicated. Understanding this region requires recognizing how colonial border-drawing affected traditional economic and social systems.

The southern Oriental Region transitions into Saharan landscapes around Figuig Oasis. This remote oasis community, split by the Moroccan-Algerian border, preserves traditional date palm cultivation and social organization patterns that demonstrate pre-national regional identities. The oasis architecture and water management systems show adaptations to extreme aridity that differ from techniques developed in other Moroccan oases.

Mineral resources, particularly around Jerada, created boom-and-bust economic cycles that shaped regional development patterns. The decline of coal mining forced economic diversification that recent government investment in renewable energy and border trade infrastructure is beginning to address. These economic transitions illustrate how resource-dependent regions adapt to changing global markets.

The Oriental Region’s climate combines continental and Mediterranean influences, creating hot, dry summers and cold winters that require different agricultural adaptations than coastal or mountain regions. Cereal cultivation dominates where rainfall permits, while livestock herding becomes more important in drier areas approaching the Sahara.

Valley Systems: Morocco’s Green Corridors

Morocco’s major valleys create ribbons of intensive agriculture and settlement that connect mountain watersheds to desert or ocean destinations. Having lived in the Draa Valley, I’ve experienced how these green corridors function as complete ecosystems supporting diverse communities along their lengths.

The Draa Valley, Morocco’s longest river system, originates in High Atlas snowfields and extends southeast toward Algeria, creating a chain of oases that supported trans-Saharan trade for centuries. Each oasis along the Draa developed distinctive characteristics based on local conditions, but all share water management techniques, date palm cultivation, and social organization patterns adapted to desert margin conditions.

The Dades Valley, parallel to the Draa but shorter, demonstrates how valley systems create microclimates that support specialized agriculture. The Dades Gorges create dramatic scenery that attracts tourism, but the valley floor supports intensive cultivation of roses for perfume and medicinal uses. This combination of natural beauty and agricultural specialization illustrates how valleys balance environmental protection with economic development.

The Ziz Valley, extending south from the Middle Atlas toward Erfoud, shows how valleys connect different climate zones and cultural regions. The upper Ziz flows through temperate mountain environments supporting different crops and settlement patterns than the lower valley, which approaches full desert conditions. This environmental gradient creates cultural gradients as communities adapt to different conditions along the valley’s length.

The Ourika Valley, easily accessible from Marrakech, demonstrates how valleys near major cities develop tourism economies while maintaining agricultural functions. Traditional Berber villages in the upper Ourika combine subsistence agriculture with tourism services, creating hybrid economies that blend traditional and modern activities. This transition illustrates broader patterns of rural development in contemporary Morocco.

Oasis Systems: Morocco’s Desert Jewels

Morocco’s oasis systems represent extraordinary achievements in desert agriculture and community organization. These green islands in arid landscapes support complex societies that have adapted sophisticated technologies and social systems to extreme environmental challenges.

The Tafilalet, centered on Erfoud and Rissani, represents Morocco’s largest traditional oasis system. Fed by the Ziz River and underground springs, this oasis supported the kingdom that eventually conquered Morocco, making it historically as well as agriculturally significant. The three-story agricultural system, with date palms providing shade for fruit trees that protect ground-level vegetables and cereals, maximizes productivity from limited water resources.

Skoura Oasis, between Ouarzazate and the Atlas Mountains, demonstrates how oases balance agricultural productivity with architectural heritage. The kasbah complexes scattered throughout Skoura’s palm groves represent fortified agricultural estates that protected communities and stored harvests during uncertain times. Today, these structures attract cultural tourism while continuing to house agricultural activities.

Figuig Oasis, on the Algerian border, shows how political boundaries can divide traditional oasis communities. The oasis extends across the border, creating complex situations where families, water sources, and agricultural plots exist in different countries. This situation illustrates how artificial borders can complicate traditional resource management systems.

Understanding oasis systems requires appreciating their social organization as much as their agricultural techniques. Water distribution follows complex schedules that allocate time-based rather than volume-based rights to different users. These systems require extensive cooperation and dispute resolution mechanisms that create social cohesion essential for oasis survival.

Transitional Zones: Morocco’s Cultural Bridges

Between Morocco’s major regions lie transitional zones that blend characteristics of neighboring areas while developing their own distinct identities. These intermediate regions often receive less attention than dramatic mountains or deserts, but they play crucial roles in connecting Morocco’s diverse landscapes and cultures.

The Atlas foothills, extending along the southern edges of the High and Middle Atlas ranges, create a zone where mountain and lowland cultures interact. Communities in these areas practice mixed economies combining seasonal mountain pastoralism with lowland agriculture, creating cultural patterns distinct from purely mountain or purely lowland societies.

The Tadla-Azilal Plains, between the Middle Atlas and the Atlantic coast, represent Morocco’s most important cereal-producing region. The combination of adequate rainfall, fertile soils, and relatively flat terrain supports mechanized agriculture that feeds Morocco’s urban populations. However, the region also maintains traditional market towns and rural customs that blend Arab and Berber influences.

The Chaouia-Ouardigha region, east of Casablanca, shows how proximity to major cities transforms traditional agricultural regions. While maintaining cereal cultivation as the primary economic activity, the region increasingly provides recreational opportunities and residential alternatives for urban populations. This peri-urban development creates new cultural patterns that bridge urban and rural lifestyles.

The Gharb Plain, Morocco’s largest agricultural region, extends inland from the Atlantic coast between Rabat and Kenitra. The Sebou River and its tributaries create exceptionally fertile alluvial soils that support intensive cultivation of cereals, citrus, sugar beets, and industrial crops. This agricultural wealth made the Gharb historically important and continues to make it economically vital.

The Tensift Basin, centered on Marrakech, demonstrates how river systems create agricultural prosperity in semi-arid environments. The Tensift River, flowing from the High Atlas to the Atlantic, supports irrigation systems that allow intensive cultivation around Morocco’s former imperial capital. This combination of agricultural wealth and political importance shaped Marrakech’s development as a cultural and economic center.

The Loukkos River Valley, in northern Morocco, shows how river valleys create cultural corridors connecting mountains to coasts. The valley extends from the Rif Mountains to the Atlantic near Larache, supporting diverse agricultural activities and connecting distinct cultural regions. Traditional market towns along the valley serve as cultural exchange points between mountain Berbers and coastal Arabs.

The Sous River Basin, extending from the High Atlas to the Anti-Atlas and eventually to the Atlantic at Agadir, creates Morocco’s most important agricultural region outside the northern plains. The river system supports everything from mountain villages practicing traditional agriculture to modern export-oriented farms producing vegetables for European markets.

Border Regions: Morocco’s Peripheries

Morocco’s border regions face unique challenges and opportunities created by their peripheral positions. These areas often preserve traditional customs longer than central regions while also developing specialized economies based on border trade and resource extraction.

The Western Sahara region, south of the Anti-Atlas, represents Morocco’s most recent territorial acquisition and its most politically sensitive border. The territory’s sparse population concentrates in coastal cities like Laayoune and Dakhla, where fishing and phosphate mining create economic opportunities. The interior remains largely nomadic, with traditional pastoral communities adapting to modern border controls and economic opportunities.

The Algerian border regions, from the Mediterranean to the Sahara, demonstrate how political boundaries affect traditional cultural and economic systems. Communities along this border historically moved freely across what are now international boundaries, creating cultural continuities that transcend national borders. Modern border restrictions have forced adaptations that sometimes create economic hardships but also preserve traditional practices.

The Spanish border areas, around Ceuta and Melilla, create unique situations where European territories exist within Moroccan territory. These enclaves generate complex economic opportunities through legal and illegal cross-border trade while creating cultural tensions between traditional Moroccan communities and European administrative systems.

Regional Cuisines: Taste the Geography

Each of Morocco’s regions developed distinctive culinary traditions based on local ingredients, climate conditions, and cultural influences. Understanding regional cuisines provides insight into how geography shapes daily life in ways that tourists often miss.

Coastal regions, both Atlantic and Mediterranean, base their cuisines on fresh seafood, with techniques and preferences varying based on local species and cultural influences. The Atlantic coast favors sardines, anchovies, and other small fish, often preserved or grilled simply. Mediterranean coastal cuisine shows more Spanish influence, with dishes that incorporate olives, peppers, and tomatoes in ways that reflect Andalusian heritage.

Mountain cuisines, in both the Atlas ranges and the Rif, emphasize preserved foods that sustain communities through harsh winters. Dried fruits, nuts, preserved meats, and hardy vegetables dominate these cuisines, with cooking techniques that maximize nutrition from limited ingredients. Berber communities developed distinctive bread-making techniques using local grains and cooking methods adapted to mountain environments.

Desert and oasis cuisines center on dates, dairy products from camels and goats, and preserved foods that travel well across arid landscapes. The tagines that tourists associate with all Moroccan cuisine actually represent oasis cooking techniques designed to conserve water and fuel while maximizing flavor from limited ingredients.

Valley cuisines take advantage of intensive agriculture to create more varied and vegetable-rich dishes. The Draa, Dades, and other major valleys produce the diverse ingredients that make Moroccan cuisine internationally famous, but each valley has developed its own specialties based on local growing conditions and cultural preferences.

Climate Variations: Understanding Morocco’s Weather

Morocco’s regional diversity creates dramatically different climate patterns that affect everything from agricultural practices to architectural styles to daily rhythms of life. Understanding these climate variations helps travelers plan appropriate visits and appreciate how environment shapes culture.

The Atlantic coast enjoys Morocco’s most moderate climate, with temperatures moderated by ocean influences and rainfall concentrated in winter months. This climate supports the Mediterranean-type agriculture that feeds Morocco’s cities and provides exports to Europe. However, the southern Atlantic coast becomes increasingly arid, with desert influences creating hot, dry conditions that require different adaptations.

The Mediterranean coast experiences more extreme seasonal variations, with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters that create different agricultural and lifestyle patterns. The proximity to Europe moderates temperatures compared to interior regions, but the mountainous terrain creates microclimates that vary dramatically over short distances.

Mountain climates vary by altitude and exposure, creating complex patterns that support different economic activities and cultural practices. The High Atlas experiences true alpine conditions with snow that lasts for months, while the Anti-Atlas receives less precipitation and supports more arid-adapted communities. These climate differences within mountain regions create cultural diversity that reflects environmental adaptation.

Desert climates dominate southern and eastern Morocco, creating extreme temperature variations between day and night and between seasons. These conditions shaped the architectural styles, social organization, and economic activities that distinguish desert communities from their mountain and coastal neighbors. Understanding desert climate patterns helps appreciate the remarkable adaptations that allow human communities to thrive in such challenging environments.

Economic Geography: How Regions Make Their Living

Morocco’s economic geography reflects the natural advantages and limitations of different regions, creating patterns of specialization that have persisted from traditional times into the modern economy. Understanding these economic patterns provides insight into regional cultures and development challenges.

The Atlantic coast concentrates Morocco’s major industries, ports, and commercial activities. Casablanca serves as the economic capital, with manufacturing, finance, and services concentrated in the Atlantic coastal corridor. This economic dominance creates cultural patterns that distinguish coastal cities from interior regions, with more cosmopolitan, business-oriented lifestyles.

Agricultural regions, particularly the Atlantic plains and major river valleys, support Morocco’s food security and export agriculture. These areas developed intensive cultivation techniques and market-oriented production that contrast with subsistence agriculture common in mountain and desert regions. The wealth generated by commercial agriculture created distinctive rural cultures and town-country relationships.

Mining regions, scattered throughout Morocco but concentrated in the Atlas Mountains and eastern regions, created boom-and-bust economic cycles that shaped local cultures. Phosphate mining in the Western Sahara, coal mining in the Oriental Region, and various metal mining operations in the Atlas created industrial communities with different social patterns than purely agricultural or commercial regions.

Tourism regions, particularly around imperial cities and scenic areas, developed service economies that blend traditional hospitality customs with modern tourist industry practices. These regions face the challenge of balancing economic benefits from tourism with preservation of cultural authenticity and environmental protection.

From my years of teaching, traveling, and living across these diverse regions, I’ve learned that Morocco’s true magic lies not in any single landscape but in understanding how these different environments shaped the remarkable diversity of Moroccan cultures. Whether you’re drawn to mountain peaks or desert dunes, Atlantic waves or Mediterranean breezes, each region offers unique insights into how geography shapes human culture.

The key to appreciating Morocco’s regional diversity is recognizing that these differences aren’t just scenic variations but represent different solutions to the challenges of living in North Africa’s diverse environments. Each region developed its own architecture, cuisine, social organization, and cultural traditions based on local conditions, creating the rich tapestry that makes Morocco endlessly fascinating to explore.

As Morocco continues modernizing and integrating into global systems, these regional differences remain important for understanding how the country balances tradition with change, local identity with national unity, and environmental protection with economic development. For travelers seeking authentic experiences, appreciating these regional distinctions opens doors to deeper cultural understanding and more meaningful connections with Moroccan people and places.

Whether you’re planning a comprehensive journey across multiple regions or focusing deeply on one area that particularly appeals to you, remember that each region rewards the traveler who takes time to understand its unique character. The Morocco you’ll discover in the cedar forests of the Middle Atlas differs dramatically from the Morocco of Atlantic fishing villages or Saharan oases, yet all are authentically Moroccan in their own distinctive ways.

Author Bio

Othmane Elmohib is a Moroccan travel content creator from Casablanca with roots in Fes. After 5 years teaching English in Agdz, he now shares authentic Morocco experiences through imfrommorocco.com and moroccancivilization.com. Connect with him for sustainable travel tips and cultural insights from a local perspective.